Geoff Kelly MSc (Hons)

[ Effective date of writing: December 2007. This article was first written in August / September 2007, for publication in the October / November edition of New Zealand WineGrower. Events conspired to prevent its publication at that point, allowing revision through to the beginning of December 2007. Publication followed in three parts, starting with the February / March Vol. 11(4) issue of 2008, titled: Bordeaux, Hawkes Bay blends in New Zealand, Part II: The coming of age of Bordeaux blends in New Zealand in the April / May issue, and concluding with Part III similarly titled in the June / July issue Vol 11(6). Due to limitations of space, the account published in WineGrower varies a little from the original manuscript, now restored in full here (with capitalisation as published). If further information becomes available, for the record it seems to me useful to add it in to this version, dated and in square brackets.

The tasting of mostly 2005-vintage New Zealand Cabernet- and Merlot-dominant wines undertaken for this review has already been published on this site: 18 Dec 2007: 2005 Bordeaux and Hawkes Bay blends in New Zealand: 33 reviews ]

Scope

Some background

The 1960s

1965 McWilliams Cabernet Sauvignon, and Tom McDonald

The 1970s – quiet

The 1980s: John Buck and Michael Morris

1987: the turning point

The role of Merlot

The 1990s and The Gimblett Gravels

Present trends, and the 2005 vintage

Hawkes Bay blends

The 2005 Tastings

Brettanomyces

A London Vintage Review, with Bordeaux

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Some background

The evolution of 'Bordeaux blends' (from straight Cabernet Sauvignon through all blend variations to straight Merlot) in New Zealand: what a romantic topic that would be to develop an in-depth thesis on. We can never now know exactly what the pre-Prohibition classical all-vinifera reds of New Zealand were like, but there are reports from the times, some of which have been quoted by later authors, which suggest they were well up to standard. Scott (1964) records that in 1908, a red wine from the Te Kauwhata Viticultural Research Station won a gold medal in the London Franco-British Exhibition, for a wine "approaching the Bordeaux clarets in lightness and delicacy". And a few surviving bottles from the pre-Prohibition era have been tasted by latterday tasters attuned to older wines. Kelly (2007a) describes a 1985 tasting of a 1903 Wairarapa one (which though bottled in a claret bottle, was probably more Syrah / Pinot than Cabernet).

Thorpy (1971) records that Te Kauwhata Research Station had Cabernet Sauvignon from 1897 until 1954, when these original vines were removed. This is key information, confirming that planting stock of this variety was in fact available to winemakers through all the so-called 'hybrid era'. But it is also likely that the Mission Estate in Hawkes Bay had Cabernet through this era too, so the extent to which Te Kauwhata cuttings were used remains to be established.

Earliest days in the development of New Zealand wine are described by Dick Scott, and later by Michael Cooper (see below) and other authors. For this account, two important pioneers in the emergence of Cabernet Sauvignon and Bordeaux-styled blends in New Zealand were the Society of Mary Mission Estate, in Hawkes Bay from the 1890s and still practising, and the now-iconic New Zealand winemaker Tom McDonald, who in 1927 bought the Hawkes Bay Taradale vineyard of the former Brother Steinmetz. He had left the Mission in 1897. Tom renamed the vineyard McDonald's, which in turn became McWilliams, and is now part of Pernod-Ricard / Montana (hence their premium label now, 'Tom'). When exactly Tom became enamoured of the Bordeaux winestyle remains to be established, but by 1949 he was producing a Cabernet Sauvignon which the late great European wine man André Simon described (quoted by Thorpy, 1971) as "rare and convincing proof that New Zealand can bring forth table wines of a very high standard of quality". Later Tom was well known for his love of the subtle Margaux winestyle in particular, and held these wines up as the model we should strive for in New Zealand.

The 1960s

Thorpy goes on to record that the only two bottles of New Zealand wine André Simon took away from here at the end of his 1964 tour were the 1949 McDonald's Cabernet, and a 1955 Cabernet made by Alex Corban. Corbans continued with a wine labelled Cabernet for several vintages, through into the 1960s. There was also a very successful Dry Red, which sometimes contained some Cabernet. Several vintages won gold medals in the National Wine Competition, though I must record that it was a different era then, and all-hybrid dry reds could win top medals. Corbans Cabernet did not reach the point of new oak elevage. Then as now, the climatic difficulties of the Henderson district would have militated against consistent quality interpretations of the Bordeaux blended style, if all the fruit had been grown there. Corbans later had large vineyards in the slightly drier zones of Riverlea and Kumeu to draw on.

Another well-known Auckland pioneer of vinifera dry reds at the time was Dudley Russell, at Western Vineyards in the Henderson district. There was a wine labelled Cabernet Sauvignon in the 1960s, but whether it was all-Cabernet, or even all-vinifera, was never quite clear. It always tasted a little murky. Bottles are still available, if modern DNA or other analysis methods can elucidate this. The vineyard no longer exists. Otherwise, wines labelled Cabernet are conspicuously missing from the National Wine Competition results of the time. Other Auckland district vineyards may have had some Cabernet, and blended it into their Dry Red. Ian Clark recalls Markovina as an example.

In Hawkes Bay, Tom's wine did continue, as McDonald's Cabernet, intermittently through the 1950s into the earliest 1960s. During this time the Mission had continued with Cabernet in the vineyard, but very little ended up as dry red. At one stage the Dry Red was dominated by Pinot Meunier, but perhaps in the later 1950s and certainly in the mid-1960s, there was a Cabernet-based Mission Claret, which I remember fondly.

It is hard to imagine now, what some of the truly awful Seibel-based dry reds of the 1950s and 1960s were like, in a New Zealand wine world dominated by fortified wines. And compared with now, with a surfeit of table wines from almost every country in the world on our shelves, nor can we imagine what our wine industry was like under rigorous import controls. Those controls encouraged the local industry, but also allowed them to ignore world standards for table wine. For the increasing number of people after the Second World War who had had the opportunity to become familiar with even the everyday wines of Europe, those years were dire. These phases are well described by Michael Cooper in the various iterations of his The Wines and Vineyards of New Zealand, starting in 1984 and culminating in his Wine Atlas of New Zealand, 2002.

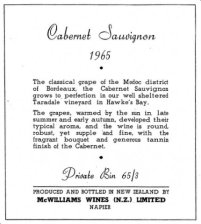

1965 McWilliams Cabernet Sauvignon, and Tom McDonald

McWilliams of Australia decided to establish in New Zealand in the mid-1940s, and established their first vineyard in 1947. In 1961/62 they bought the vineyard of Tom McDonald at Taradale, and Tom headed McWilliams New Zealand. In the 1950s the firm designed a dry red conforming a little more to international expectations of the style, basing it on Baco No 1 and Seibel 5455, two more vinifera-like hybrids than most Seibels. A little Cabernet Sauvignon was added in some years. This wine was named Bakano. It was launched in either 1954 or 1956, and became New Zealand's most reliable and popular dry red, as wine-drinking gradually became an accepted (if minority) part of life in New Zealand. It was at best pleasant drinking, no doubt depending on exactly how much Cabernet was in the particular year. Its quality as a red wine was seen to be endorsed by its wholesale adoption both by the Italian tunnellers then engaged on the Turangi power scheme, and also by the 1964 vintage being selected as house wine by the touring French rugby team of 1968.

I imagine it was always a tussle, though, as to how much of Tom's beloved Cabernet would be squandered to commercial reality under pressure of the Australian principals, and how much could be put aside for Tom's goals. I imagine not much, when Bakano was at its zenith, from 1958 to 1964. Certainly McDonald's Cabernet had become very rare indeed by then – what years were actually made or commercialised needs to be established, while some of the people involved are still alive. The same applies to the development of Bakano. And it is important to remember that though Tom McDonald is now lionised, not all his wines were clearly a cut above the New Zealand average. Though the 1949 and 1951 Cabernet have passed into wine folklore, the Cabernet was not made in most of the 50s. There was a 1962 McWilliams Cabernet Sauvignon, for example, which failed to win high award, at a time when Bakano was winning Gold Medals.

A key issue in those days was, winemakers had become habituated to the yields of the hybrids, at many tonnes per acre, and there was a widespread view that vinifera-based dry reds could not possibly be made profitably in New Zealand. To have any colour or taste, they had to be cropped at unthinkable rates of 2 – 4 tonnes per acre. Also by then, many winemakers were not familiar with what that 'taste' of red wine should be, since under import control the drinking of imported red wine was unusual, and seen to be elitist. These views had grown through 40 years, since Prohibition, and so were entrenched by the 1950s. Hybrid reds had become the norm, despite the all-vinifera start in the late 1800s.

All this started to change in 1965, when rumours spread that Tom McDonald had again made a Cabernet Sauvignon, now under the McWilliams label. Rumour further said that Tom had been permitted to purchase one new barrel, to assist its maturation. Dennis Robinson confirms the 'one' is apocryphal, and Bob Knappstein estimates there may have been 5 or so puncheons of the wine. The new oak (American) was certainly noticeable in the young wine. All this crystallised when a wine named 1965 McWilliams Cabernet Sauvignon Bin 65/3 was entered in the Trade & Industry National Wine Competition of 1967, and won the only gold medal for Dry Reds. It repeated the achievement in 1968, but had to share the ranking with Corbans Dry Red.

It was finally released in spring 1969, at $1.40 per bottle. Well do I remember this first publicly-known New Zealand Cabernet Sauvignon being offered for sale. Well, offered for sale is an over-statement. In fact you had to write to Tom McDonald himself, and seek to book a case prior to release. Not all applicants succeeded! The only way one knew the wine existed was thanks to the Trade & Industry National Wine Competition booklet published after the judging, plus perhaps newspaper reports of those results, remembering that wine was yet to become popular, and the papers did not cover wine judgings as much as in the 1980s.

In those more leisurely days, when to drink proper Bordeaux under 10 years of age was: 'a sin against the spirit of the bottle' (according to the English), this McWilliams wine was not released until more than four years after harvest. And what a performance physically securing it was. Having been approved by Tom himself, at that time all such freight was required by law to be sent by New Zealand Railways. The winery posted the invoice, so you knew it was on its way, but it was extraordinary if you saw the wine inside a week from despatch. And then of course you had to go to the railway station to collect it. Ringing the freight department of your nearest railway station to check the carton's arrival was a daily chore – to ensure speedy pick-up. Anything to lessen the chance of the almost inescapable breakages, in Railways' care. It seems unbelievable now, when from Wellington one can order wine from Auckland as late as 3 pm one day, and it will be delivered to your front door before 9 am the following day, almost invariably intact.

The 1965 McWilliams Cabernet Sauvignon is described by Thorpy as: "The 1965 is, in my opinion, the finest commercial wine made in my lifetime in New Zealand, and the forerunner of what I think will be the grand naissance of New Zealand wines. ... It has a true Cabernet Sauvignon bouquet, reminiscent of flowers and fruit, and although it

will not be at its best for another five or ten years, it has the characteristics of great claret." That was written in 1971 – prophetic words. Bob Knappstein, who joined McWilliams in 1974, concurs. He has tasted the earlier wines, and in discussion is very clear the 1965 fully matched or bettered the earlier famous McDonald's wines.

will not be at its best for another five or ten years, it has the characteristics of great claret." That was written in 1971 – prophetic words. Bob Knappstein, who joined McWilliams in 1974, concurs. He has tasted the earlier wines, and in discussion is very clear the 1965 fully matched or bettered the earlier famous McDonald's wines.

In my view that 1965 wine was never again quite matched by McWilliams, though some consider good bottles of the 1969 were at least its equal. Some of the 1969s tended unstable in bottle, as if a little MLF were being completed. Presumably it was not assembled into one blend, before being bottled. The 1966 was better than the 1965 in the sense that the American oak was a year old, so the new oak was less noticeable, but the fruit lacked the lovely depth and ripeness of the 1965, and the wine was a little more acid. The 1967 likewise was more acid, and industry folklore has it that its increased richness owed something to an admixture of one of the few vinifera (near-vinifera) reds available, Chambourcin. No-one is sure, now.

Then in 1968, with the clamour to secure this wine, McWilliams decided to 'go commercial' with the Cabernet Sauvignon. The label changed from a simple text statement on plain paper indeed suggesting a Private Bin, to a more conventional illustrated one. The volume of the wine available increased somewhat, and the wine itself became lighter. The 1969 (see above) and 1971 (to a degree) were again more concentrated, though not to compare with the 1965. Alex Corban suggests, and Dennis Robinson confirms, that the quality of these three vintages coincides with the first crop off newly-planted vineyards. In particular, the 1969 represents the debut of the Tukituki vineyard. 1972 was a very poor year climatically, and from that point on volume increased and the label became more frankly commercial, sad to say. It petered out in the mid-80s, as a Cabernet / Merlot label.

If younger wine people would like some inkling of what the best McWilliams Cabernets tasted like in the 60s, one of the wines offered for review, 2005 Passage Rock Cabernet / Merlot Reserve, is uncannily like them – both in fruit ripeness achieved, and from significant American oak.

All of the McWilliams Cabernets from 1965 to 1971 remain pleasantly drinkable to this day, but they are now very light, very dry, and very fragile – as are the 1967 Bordeaux for example. That has to be accepted, in evaluating them now. Many younger people habituated to the dark, thick and sometimes not bone-dry wines of the present-day Australian-influenced wine marketplace find fair appraisal of them difficult, now. They cannot believe those wines were absolute shining beacons of their day, lighthouse wines to lead us out of the 1950s and 1960s New Zealand world of red wines made from the execrable Seibel hybrids, and the slightly more acceptable Baco No 1.

The 1970s – quiet

But if people today find it hard to see the quality in those early McDonald's / McWilliams Cabernets, one or two critical thinkers of the time had no trouble. Nick Nobilo promptly planted Cabernet at Huapai a little north of Henderson, a district fractionally more suited than Henderson to developing appropriate physiological maturity in the Bordeaux varieties, at least in the best years. His 1970 Cabernet Sauvignon was a very serious wine indeed, though perhaps it benefitted from the first crop syndrome, whereby the quality achieved in that first harvest is not again re-captured for seven or so years. His Pinotage of that year was also remarkable, showing that appropriately cropped and vinified, this grape could make a distinguished red in New Zealand. Both benefitted from French oak, rather than the American at McWilliams. Nobilo Cabernet Sauvignons continued through the 1970s, and were 'correct', if sometimes light. The 1976s however were again magnificent, key wines in the evolution of quality New Zealand reds

Further south, the fledgling wine company Montana planted Cabernet at Mangatangi south of the Pokeno Hills, Auckland, and the Australian company Penfolds was developing a presence in Hawkes Bay. About 1974 Montana started planting Cabernet in Marlborough. All of these were to prove detours on the path to New Zealand Cabernet blends, though the first Montana Cabernet Sauvignon from the 1973 vintage created interest, since the Reserve version (distinguished only by the diagonal banding on the neck capsule!) won gold medal.

I say detours, because neither of the districts chosen by Montana was climatically optimal for the development of full physiological flavour maturity in the grape. This was exacerbated by the cropping rates of the day. Nothing inhibits the development of full flavour maturity more than over-cropping. And it is true to say, the threshold for achieving gold medals in New Zealand judgings was then very different from today. For example, the 1973 Montana two were very similar, the Reserve being perhaps a barrel selection and just a little richer. In style they were like a light cru bourgeois from the northernmost Medoc. The Penfolds foray into New Zealand was abandoned. [ Note added 7/08: Peter Hubscher advises these two Montana wines were made from Gisborne fruit, the standard wine CS 85% and Me 15, the Reserve CS 100%, both raised in American oak coopered in France. 1973 was a drought year, helping the achievement of ripe flavours in this district where in many years Cabernet (and even Merlot) does not ripen fully. ]

In 1976, Joe Babich introduced a Cabernet Sauvignon label, based on Henderson-grown fruit. Then as now however, the Henderson district was not suited to developing appropriate Cabernet flavours, and the wines were leafy / stalky. That was accepted, at the time.

Meanwhile, during the 1970s, Hawkes Bay was quietly consolidating its position. Future prominent winemakers such as Peter Robertson of Brookfields were then gaining wine industry experience in one way or another. But there were few memorable wines. McWilliams was in a very commercial phase. Import control was rife. Wine standards stood still, or maybe retreated. This was the era of the water into wine phenomenon, to be righted in 1980, which others have documented – see for example Cooper again. The lesson of the McDonald Cabernets had not been forgotten, however.

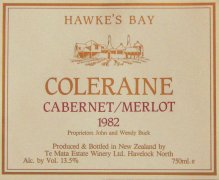

The 1980s: John Buck and Michael Morris

One key figure in the emergence of Hawkes Bay as the premier red wine district of New Zealand (Pinot aside) was John Buck, who came back to New Zealand from wine trade experience in London, with a palate attuned to the tastes of real red wine made solely from vinifera grapes. He, like Tom McDonald, was captivated by the Bordeaux style. He teamed up with Wellington wine man Michael Morris, and gradually the concept of establishing a vineyard dedicated to a New Zealand interpretation of the Bordeaux blend was born. Their purchase of the historic Te Mata Vineyard at Havelock North was completed in 1974, and their goal to make a wine in the Bordeaux and more specifically Medoc style was under way. The first wine to be labelled Cabernet Sauvignon appeared in 1980, and immediately served notice that something special was afoot. Then came the 1982 and 1983 Te Mata Awatea and Coleraine, the former

more Cabernet then, the latter a Cabernet / Merlot blend. These were the greatest post-Prohibition achievements with the style since the Tom McDonald wines, culminating in his 1965 McWilliams. They were much more widely appreciated too, more classical with French oak, and widely written up both in New Zealand and Australia.

more Cabernet then, the latter a Cabernet / Merlot blend. These were the greatest post-Prohibition achievements with the style since the Tom McDonald wines, culminating in his 1965 McWilliams. They were much more widely appreciated too, more classical with French oak, and widely written up both in New Zealand and Australia.

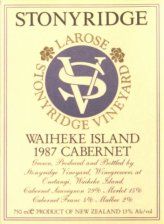

Since those Te Mata wines were launched in the quiet red wine times of the mid-80s, the tempo of development in New Zealand red wine has been phenomenal. I cannot document it here, having preferred to touch on the earlier years, but it would make a great story. Hawkes Bay in particular has gone from strength to strength. But most importantly, pioneers had been planting on Waiheke Island. Initial vintages were modest, but from the 1987 vintage, suddenly almost out of nowhere, exciting wines totally in a Bordeaux mould appeared from both Stonyridge and Goldwater. Also in the mid-80s, great things were reputed from Cabernet blends grown in the Matakana district by the Vuletic family. First there was a wine named Antipodean, and latterly one named Providence. Since these wines appear to never be assessed in conditions allowing critical blind evaluation with comparable wines, information on them is scarce. The only one I have tasted is the 1987, which was rich but tending eccentric.

1987: the turning point

1987 was the marker year in the evolution of Bordeaux-styled reds in New Zealand. For the first time, not one but several wineries produced wines of near-international quality. One would like to think that as people tasted the 1982 and 1983 Te Mata offerings, gradually the realisation dawned that to achieve those plump flavours of full physiological maturity in the grape, then perhaps there was something to all this French nonsense about appellation controlée limits on yield determining wine quality. Odd wines apart (some mentioned above), we had never seen those flavours before in New Zealand (in the recent wine era). This topic really needs exploring, while many of the principal players are still around.

1987 was not at the time seen as an exceptional season, in Hawkes Bay. It was on Waiheke, however. But when wines such as the 1987 Villa Maria Cabernet and Cabernet / Merlot Reserves started to appear, I wrote a series of reviews in National Business Review about the 1987 New Zealand reds, in the concluding one stating: "The results were clearcut. Stonyridge Larose is New Zealand's top red in the 1987 vintage. It joins a shortlist of all-time great New Zealand Cabernet styles, such as 1965 McWilliams Cabernet Sauvignon, and the 1982 and 1983 Te Mata reds".

Each wine I rated highly, I bought a case to allow subsequent checking of its evolution. They have been the subject of several stimulating subsequent Library Tastings in Wellington. The most recent of these evaluations in November 2002 showed the 1987 Stonyridge Larose is still sensational, quite eclipsing the Fourth Growth 1987 Ch Talbot

put in as a marker. The 1987 Stonyridge is of Second or First Growth standard, for the year. Other wines still showing well, in the sense of lesser classed growth or cru bourgeois wines, were 1987 Villa Maria Cabernet Sauvignon / Merlot Reserve, 1987 Goldwater Cabernet / Merlot / Franc, 1987 Vidal Cabernet Sauvignon / Merlot Reserve, 1987 Villa Maria Cabernet Sauvignon Reserve, and in a more leafy way, 1987 Matua Merlot. The 1987 Te Mata reds did not show well, the winery having a dip after the earlier successes, and not coming back on form until 1989. And it must be remembered, New Zealand like Bordeaux is a marginal climate for quality red wines, so variation year to year is to be expected. That is one reason why our best years are so good, when compared with the wines of more uniform warmer climates.

put in as a marker. The 1987 Stonyridge is of Second or First Growth standard, for the year. Other wines still showing well, in the sense of lesser classed growth or cru bourgeois wines, were 1987 Villa Maria Cabernet Sauvignon / Merlot Reserve, 1987 Goldwater Cabernet / Merlot / Franc, 1987 Vidal Cabernet Sauvignon / Merlot Reserve, 1987 Villa Maria Cabernet Sauvignon Reserve, and in a more leafy way, 1987 Matua Merlot. The 1987 Te Mata reds did not show well, the winery having a dip after the earlier successes, and not coming back on form until 1989. And it must be remembered, New Zealand like Bordeaux is a marginal climate for quality red wines, so variation year to year is to be expected. That is one reason why our best years are so good, when compared with the wines of more uniform warmer climates.

The role of Merlot

The other key development of the 1980s was the appearance of Merlot. Up till 1981, Cabernet Sauvignon was the buzzword, and everybody wanted wines labelled thus. But it was clear that even in the premium Bordeaux blends district of Hawkes Bay it was difficult to achieve the smells and flavours of full physiological maturity at all consistently. As noted above, we were then as a country very accepting of leafyness, or worse, green tinges in our Bordeaux blends. But as always, the French were there before us, and the evidence of Merlot on the right bank of Bordeaux was hard to ignore. The first straight Merlots commercially released were made by Michael Brajkovich at Kumeu, and Denis Irwin / Matawhero in Gisborne, both in 1983. And there was the hard evidence of the superb 1982 and 1983 Coleraines.

By 1987, it was appropriate to write a review for National Business Review titled: "Ripe Fruit needed for Cabernets", which concluded with the following section: "Ripeness: Two conclusions emerge from these 1985 New Zealand claret styles. To have our Cabernet / Merlots recognised as world class will require ripe fruit, riper than almost all the reds thus far picked in New Zealand. They must taste ripe, not just be sugar-ripe. Tasting ripe means soft tannins, with no green edges. Secondly, to have our claret styles achieve consistent standing offshore requires Merlot. Over the 10-year weather span of a normal decade, the softer flavours of more easily ripened Merlot will be essential, if our wines are to achieve pleasing complexity. Rather like Pinot Noir, Merlot is more demanding than the versatile Cabernet Sauvignon, but ultimately it will be more rewarding." Now, straight Merlots are more common than straight Cabernets.

This advocating of Merlot is relative. It should not be taken to mean replacing Cabernet completely, though certainly recent planting statistics show Merlot has quintupled in the last 10 years, while Cabernet has almost stood still. We must keep in mind that New Zealand is uniquely placed to produce classical Bordeaux styles, and traditionally that means light, fragrant and floral cassis-oriented wines. The wines of the Bordeaux west bank, with Cabernet prominent, have traditionally always been the most esteemed in the British market. It is only in the last 20 years, under the influence of American commentators who prefer bigger, softer, fatter, wines, that the Pomerol district particularly with its Merlot-dominant cepages, and St Emilion to a degree, have become so fashionable. We must not throw out the baby with the bathwater.

We will be wise therefore to continue to strive for the more complex Cabernet-influenced and Medoc-styled Bordeaux blends on sites which can optimise full physiological flavour maturity in Cabernet, in the vineyard. Cepage in Medoc blends varies, ranging up to 90% Cabernet sometimes, but about half adds to the aromatics enormously, with Merlot building in plummy soft richness, mouthfeel, and stuffing. But as Bordeaux again shows, there is a great role for straight or Merlot-dominant wines too, and the number of New Zealand examples in our market-place has grown. Wines such as Kate Radburnd's 1998 Pask Merlot Reserve initially set the pace, and it has now been joined by totally international-calibre wines from Sacred Hill, Esk Valley and Villa Maria, to name a few. We need to be very confident about our Merlot, for even moreso than Cabernet, we have one of the few world climates which can ripen the grape to its full delicately floral yet velvety rich complexity, without sur-maturité. In this capability, good New Zealand Merlot is an analogue of our Pinot. Comparative tasting with virtually any Australian Merlot hammers this point home.

In addition to Merlot, the other famous Bordeaux-blend grapes were not entirely forgotten. Morris and Buck had planted Cabernet Franc, as did both the Goldwaters and Stephen White (Stonyridge) on Waiheke. Some also experimented with Petit Verdot, though with its reputation in France as being harder to get properly ripe than Cabernet, the logic of it for New Zealand remains debatable. Malbec also has been planted by many, even though it is out of favour in Bordeaux. It is a versatile grape, in Gordon Russell's experience ripening fractionally earlier than Merlot, and significantly earlier than the Cabernets. In truth it is also less fine than the premium grapes, or more robust, depending on how one wants to look at it. Later on, Malbec was to be the dominant planting in the development of the vineyard now known as The Terraces, Esk Valley's rare premium wine, which many consider their best. The jury is out, on that one.

The 1990s and The Gimblett Gravels

By the end of the 1980s, and into the 1990s, Hawkes Bay and Waiheke had emerged as our two viticultural districts best suited to New Zealand interpretations of the Bordeaux blended winestyle. But New Zealanders are contrary people, and though Montana's efforts with the Cabernet half of the Marlborough equation were subsiding by then, they persisted with Merlot. By now there were other pioneers exploring the Bordeaux blends in districts ranging from northernmost North Auckland through to Waipara, in northern Canterbury. In-between there are vineyards dedicated to the style in Matakana and Clevedon in the wider Auckland district, Martinborough, and Marlborough, some adopting extreme viticultural practices to ripen the fruit.

The years 1989 to 1991 produced some good red wines, which consolidated the tentative steps of 1987. In particular, Te Mata returned to form, with 1991 reds which could be compared with the earlier 1982 and 1983 wines. Villa Maria, Vidal Estate and Esk Valley continued their steady trend of improvement particularly in Hawkes Bay, though Villa Maria also had some quite exceptional Cabernet Sauvignons, achieving full flavour ripeness at very low Brixes, from their Mangere Ihumatao Vineyard. But this improving trend was brought to an abrupt halt by the June 1991 eruption of Mt Pinatubo in the Philippines. This was the largest explosive volcanic eruption the Earth had known since Krakatoa in 1883. It ejected vast volumes of ash and gaseous matter into the atmosphere and stratosphere, such that for at least two vintages thereafter, Earth was up to half a degree Celsius cooler. In a marginal viticultural zone such as New Zealand, the impact was dramatic. There were few if any memorable Bordeaux blends made in those years.

But the key development of the 1990s was the gradual recognition that an area of stony 'barren' land in the Gimblett Road area of inland Hawkes Bay had exceptional potential to ripen red grapes to a degree not hitherto achieved consistently in New Zealand. This area could be recognised by the passer-by as about the only place in the North Island where the Californian poppy Eschscholzia californica grew wild, and the penny should have dropped earlier. But it took top-dressing pilot (and part-time grape grower) Chris Pask, who flew over the area regularly, to put two and two together, and buy the first parcel of land for grapes in 1981. He was followed in 1983 by soil chemist Dr Alan Limmer, of Syrah fame. Pask was a contract grape grower for Villa Maria group, and their purchase of land in the zone quickly followed. By the 1990s they were joined by Babich and other companies, and the rush for a share in this exciting 'terroir' was on.

Extravagant claims have been made as to the warmer temperatures experienced on the Gimblett Gravels, the website www.gimblettgravels.com itself claiming the growing season average temperatures are up to 3°C warmer than other parts of Hawkes Bay. Growers in other parts of Hawkes Bay hotly dispute such claims, and there is a certain amount of friction in the district, as premium winemakers jostle for sales in the limited market for over-$30 bottles. Careful analytical studies over a five-year or similar base remain to be done, but what does seem indisputable is grape vines bud and burst and start growing several weeks earlier, and viticulturists can therefore achieve either a longer growing season, or bring the grape crop to maturity earlier in the season, perhaps avoiding difficult weather in later autumn.

From the wine enthusiasts point of view, it is also indisputable that in 1998, one of our hottest years to date, some of the Gimblett Gravels grapes suffered from sur-maturité – over-ripening – and produced wines inclining to an Australian style, heavier, plummier, but lacking in the lighter floral components of bouquet and palate which differentiate subtle European wines from heavier Californian or Australian ones. Whilst the populist market thinks heavier riper wines are by definition better, this is most certainly not the case for the premium sector New Zealand is aiming for, if growers are to crack the discerning European market for red wines. Hot years such as 2003 in Europe are not rated as highly, though this is changing under the pervasive influence of American wine commentators, who favour bigger and heavier wines. For grapes such as Merlot and Syrah, which are particularly prone to over-ripeness, already some of our leading winestyles from Hawkes Bay are either being grown off the Gravels, or with a thoughtful admixture of grapes from elsewhere in the Bay, to add florality particularly. What a remarkable change this is, to have to consider red varieties being over-ripe in New Zealand, when a mere two decades before, in the 1978 vintage, all the Cabernet wines including the gold medal ones were green and stalky.

So there is much still to be told about the merits and demerits of the Gimblett Gravels, but there is no doubt it is an exciting sub-zone within the Hawkes Bay viticultural district. Growers incorporated themselves into the Gimblett Gravels Winegrowers Association in 2001, defining the zone strictly on mappable soil criteria, and registered Gimblett Gravels as a trademark. The area amounts to 800 ha, and is already 70% planted to grapes.

Present trends, and the 2005 vintage

Since the unusually hot 1998 vintage, New Zealand has had a fortunate run of vintages. None have been disastrous in the Cabernet / Merlot zones. Vintage 2002 was particularly favourable in Hawkes Bay, and very good elsewhere. Those wines are no longer commonly available. The next generally very good vintage is 2005, so that was selected as the basis to assess current achievements for this review.

2005 was an exciting late summer for North Island New Zealand growers of Hawkes Bay / Bordeaux blends. Stephen White from Stonyridge Vineyards, Waiheke Island, and in Hawkes Bay both John Buck, Te Mata Vineyards, and Steve Smith, Craggy Range Vineyards, all imply or say that their best 2005 reds are the best yet:

White: " ... one of the hottest and driest seasons on record ... regarded by all the winemakers on Waiheke as the finest vintage ever."

Buck: "We believe this 2005 vintage to be the finest Coleraine yet produced ... berries were the smallest on record ... the quality of the grapes ... exceptional."

Smith: "Our Gimblett Gravels red wines from 2005 represent our greatest ever red wine vintage and are the best young reds I have ever seen in New Zealand."

These are pretty big claims, which cry out for examination. Accordingly therefore, for this review, a far from comprehensive cross-section of a few labels that may be contenders for the concept 'top New Zealand Bordeaux / Hawkes Bay blend for 2005' was assembled, plus a few others to achieve geographic representation. Where wines were bottled but not yet on the market, supportive proprietors supplied pre-release bottles – a much appreciated gesture. In pursuing these wines, it became apparent that not everybody agreed the vintage was ideal.

Stonyridge were in no doubt for Waiheke, as above. In Hawkes Bay however the vintage seemed perfect till March 17, when the first of three isolated rainfalls occurred. From then on, there was some luck for each vineyard in where the rains fell, the crop they were carrying, the degree of leaf-plucking, the degree of maturity in each vineyard when it rained etc etc, as to how the fruit came in. Te Mata and Craggy Range feel as above; Trinity Hill for example will make no Homage series reds. So not all the expected vineyards are represented in the batch below. And some prefer not to participate.

The 2005 Tastings

For this review, wines from Cape Karikari to Marlborough were included in two tastings, one in May and one in September. The results are exciting. I have been assessing the quality of Cabernet and Merlot-dominant wines from France and then New Zealand since the 1962 vintage. In New Zealand one cannot hope to achieve a fraction of the coverage the United Kingdom wine people do, and I cannot claim assessment of every vintage. But the assessments have been careful, written, and for the last 25 years, often blind. And from that experience I can only agree with the view offered by Steve Smith of Craggy Range, that the best of these 2005 New Zealand Bordeaux blends include our greatest red wine achievements yet. There are some 2002 and 2000 wines that are pretty stunning, but the best of these

2005s show a critical ripeness of fruit which retains florality, yet displays perfect physiological maturity and a quality of berry-complexity only temperate-climate Bordeaux consistently achieves. And finally, there is restraint in the oak handling, in our better wines. Gradually we are moving from brash new world winemaking to blending the best of new world technology with some of the finesse and subtlety of the old.

2005s show a critical ripeness of fruit which retains florality, yet displays perfect physiological maturity and a quality of berry-complexity only temperate-climate Bordeaux consistently achieves. And finally, there is restraint in the oak handling, in our better wines. Gradually we are moving from brash new world winemaking to blending the best of new world technology with some of the finesse and subtlety of the old.

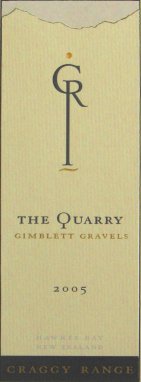

And how good are the best wines, in comparison with some of the famous wines of France? I suggest the best are of classed growth standard, and the very best match some of the Second Growths. The top wine of the tasting, 2005 Tom from the Church Road winery of Pernod-Ricard, has an extraordinarily Leoville-like quality to it. I will leave which Leoville open, to tease readers into setting up their own blind tastings, once 2005 Tom is released, and the eagerly-awaited 2005 Bordeaux reds arrive. But what a thrill it is to see the wine named to honour the memory of Tom McDonald finally achieve a stature worthy of him. Early vintages were both leafy and bretty, but 2002 marked a worthwhile step forward. This 2005 is truly memorable. It may be our greatest red wine so far.

The other exciting thing is, quite a handful of our wines easily match and surpass well-known Cru Bourgeois and lesser classed growth Bordeaux labels such as Ch Potensac, Ch Cantemerle, Ch Cantenac-Brown, and even the Rothschild-owned Ch Duhart-Milon. This means our wines can be marketed confidently, in a price band that is much more accessible and practical than the 'investment grade' top classed growths. But in each of our better vintages now, more of our wines are achieving a standard that bears exact comparison with more famous Second, Third and Fourth Growths. The new Craggy Range winery has four labels in 2005 which display this standard – an astonishing achievement. As more of our premium wines achieve dry extracts nearer the European quality target of 30 grams per litre excluding sugar, so will more of them match their top wines. Below I suggest a London tasting each year, to help build a reputation for our wines in the critical British wine market and wine-writing base.

Though the results confirm that Hawkes Bay dominates, and Waiheke has much to offer also (though at peril of being in a slightly leafier and cooler style – a comment that also applies to nearby Clevedon), it is only fair to comment on a couple of pioneers outside those zones. The Karikari Peninsula wines confirm that in terms of their Bordeaux styling and ripe flavours achieved at low alcohols, certain districts in North Auckland and presumably Great Barrier Island below critical rainfall and humidity levels will in some years produce remarkable wines. In Martinborough the achievements of the Benfield & Delamare team must be admired. The very best years of their now Merlot-dominated blends, such as the 2003 and 1998, are truly Bordeaux look-alikes, though tending to be over-influenced by new oak. In Marlborough, the Herzog wine shows that only Merlot-dominated or straight Merlot wines have any chance, unless exceptionally sheltered sun-bowl locations can be found.

But of these southern districts, as with other varieties, it is the special sheltered characters of the Waipara district which make one wonder if the most favoured sites there, optimising all the warmth that is going, will one day (if global warming be true) make special St Emilion-styled wines. In certain years, Pegasus Bay offers a Bordeaux blend red under their Maestro label, and in years such as 1998, it can be quite remarkable.

Reviews of the 30 or so wines blind-tasted for this review have been presented at Kelly (2007b). The top dozen are all gold medal wines, in wine show terms. In approximate ranking, they are:

2005 Church Road Merlot / Cabernet Tom*

2005 Craggy Range Cabernet / Merlot The Quarry

2005 Blake Family Vineyard Merlot / Cabernet**

2005 Craggy Range Merlot / Cabernet Franc Sophia

2005 Church Road Cabernet / Merlot Reserve

2005 Sacred Hill Cabernet / Merlot Helmsman*

2005 Goldwater Cabernet / Merlot Goldie*

2005 Craggy Range Merlot / Cabernet Te Kahu

2005 Te Mata Cabernets / Merlot Coleraine

2005 Stonyridge Cabernet / Malbec / Merlot Larose

2005 C J Pask Cabernet / Merlot / Malbec Declaration*

2005 Newton Forrest Cabernet / Merlot / Malbec Cornerstone*

Wines marked with an asterisk were not released at the time of tasting. 2005 Tom will not be released till 2009, keeping the 4-year release date tradition of the original McWilliams Cabernets alive. The Goldwater and Blake wines

are 2008 releases. The others are later 2007. Villa Maria needs mention. This firm has excelled with Bordeaux blends in New Zealand for 20 years now. They entered beautifully fragrant and elegant wines, but presumably due to the localised rains of the 2005 vintage in Hawkes Bay, they were not quite as rich as this top twelve.

are 2008 releases. The others are later 2007. Villa Maria needs mention. This firm has excelled with Bordeaux blends in New Zealand for 20 years now. They entered beautifully fragrant and elegant wines, but presumably due to the localised rains of the 2005 vintage in Hawkes Bay, they were not quite as rich as this top twelve.

Special mention must be made of the Blake Family Vineyard wine, double-asterisked above. For this wine to be in the top twelve in only its third vintage under American Mark Blake's ownership and leadership must be noted. But it has been overtaken by events. That Blake has decided to terminate his New Zealand venture is an inestimable loss to New Zealand wine making, and the raising of standards here. In the brief time he was here, he showed just what could be achieved in New Zealand wine by somebody with an absolutely focussed attitude, tasting to totally international standards. The fact he had the financial reserves to buy top viticultural land on the Gimblett Gravels is not the main issue. The key point is he knew exactly what great Merlot-dominant wine should taste like, in a world context, when grown in a climate ideally suited to retaining florality and cool climate complexity in the grape, yet warm enough to ripen the fruit completely. Few New Zealand winemakers have this exact experience and perception, plus the extraordinary passion to create world-class fine wine, such as Mark Blake displayed. There is a vast difference between striving to make wines which can in fact be measured against the world's best, and setting out to market prestige wines, selling at inflated retail prices, achieved only against the New Zealand background. Such wines achieve their reputation all too often on absurd packaging, social cachet and snob value, rather than intrinsic merit. Too many of our pinot noir makers are falling into this trap, and the first vintages of Tom did likewise. Mark Blake did not make these mistakes. His departing our shores is a great loss to the New Zealand wine industry generally, and our emerging Bordeaux / Hawkes Bay blends in particular. The future of this particular wine is unknown. [ Note added 7/08: it will be released in September 2008, as 2005 Blake Family Vineyard [ Merlot / Cabernet ] Redd Gravels, at c. NZ$80. It will be available at least from Caro's in Auckland, and Regional Wines & Spirits, in Wellington ]

Hawkes Bay blends

Meanwhile, considering the much-used term 'Bordeaux blend', and at risk of upsetting the Waiheke people, there does seem to be a very good case for us to be optimising the concept of 'Hawkes Bay blend', and promulgating it. Not only does this get us out from under the skirts of Europe, but it allows us to develop an individual winestyle, as the Italians are so successfully doing with their various 'super-Tuscans'. The addition of Syrah is the obvious tactic, to increase the florality of the wines, and add to its appeal in European markets.

Brettanomyces

The role of Brettanomyces (brett) needs mentioning. Moderation is needed here. Australia under the influence of the Australian Wine Research Institute is rapidly becoming obsessive / absolutist about this fragrant little yeast, and many in New Zealand are following in their footsteps. But the fact of the matter is, wines such as Second Growth Ch Leoville-Barton, regarded by all right-thinking British wine merchants as the absolutely definitive Bordeaux to invest in for pleasure or profit, and invariably selling out in every half-decent vintage, shows brett in many vintages. Its popularity is undiminished.

Thus, assessing and ranking the wines for this tasting, particularly with the thought of a Top 10 or similar for my London suggestion below, has been a 'walking on coals' affair. So many winemakers will categorically object to a wine such as the Goldwater Goldie, clearly bretty, being shown in London. Yet the absolute Bordeaux style, the complexity of bouquet, and the quality of plump round fruit on palate that this wine displays is exceptional. Coupled with sensitive handling of the potentially cedary oak, this is a wine British wine-merchants will love. Similarly, many allegedly premium Californian wines are clearly bretty. So why make it hard for ourselves? This 2005 Goldie is a magnificent wine in style. And wine ultimately is about beauty and enjoyment, to which technology must be servant, not master.

A London Vintage Review, with Bordeaux

The time has arrived when we can promote our Bordeaux / Hawkes Bay blends confidently. Once the 2005 Bordeaux are available, I would like to see a very focussed tasting of the top 2005 New Zealand wines presented in London, taking for example eight of the top wines listed above, and presenting them interleaved with eight very carefully selected 2005 Bordeaux reds in a fully blind tasting, to a critically selected 18 or so wine trade writers. This tasting must be co-ordinated and presented to a degree I have never seen fully achieved by the trade in New Zealand. That means all the wines standing upright for at least a week before the tasting, the wines being carefully decanted off the sediment over a light, several hours beforehand, into another set of uniform bottles, numbered. It staggers me how commonly wine people believe decanting means pouring out the entire bottle. And presentation in uniform bottles is essential, to prevent shrewd tasters picking up that the non-conforming tall show-off bottles are the New Zealand ones. The wines must then be warmed to a uniform ambient, and all presented together in one flight. But that is not all that is needed. Once tasting is done, the discussion and commentary on those wines needs to be convened in a way that obliges tasters to vote on the ranking of the wines before they are unveiled. This can be made fun, if done lightly enough.

Selection of the Bordeaux wines is critical. It must be done on taste, to match and optimise the New Zealand wines. There should be one from each principal district, and they should NOT be First Growths or clearcut super-Seconds like Leoville-Las-Cases. Reality should prevail, and some should match the price bands we are aiming for. But each of the wines chosen should be well-known. And we would be wise to select one or two wines which will actually illuminate the quality of New Zealand fruit. So while well-known cru bourgeois and minor classed growths such as Ch Potensac and Ch Cantemerle would be valuable, we should also include wines such as the Second Growth Ch Pichon-Lalande, the St Emilion Ch Figeac, and a famous St Estephe less opulent than recent examples of Ch Cos d'Estournel. Choosing the wines requires immense attention to tasting detail, as will convening the discussion. Such an exercise presented annually in London could become a very valuable forum to display New Zealand's actual achievements with the Bordeaux style, and the Bordeaux-like vintage variation we also display. And I would love to see some of their faces, when the labels are revealed.

Conclusion

Watching the evolution of our Cabernet and now Cabernet and Merlot blends over the last 40 years has been immensely exciting. The progress is little short of stunning. Yet listening to people like Steve Smith at Craggy Range, Tony Bish at Sacred Hill, and Alastair Maling in Villa Maria group, it is more than obvious that the next 40 years will make current achievements feel like infancy.

As others including in the United Kingdom have documented, Hawkes Bay and Waiheke are two of the very few places in the world where Merlot / Cabernet wines of infinite subtlety, finesse, and floral complexity can be made, wines which despite their depth remain light and refreshing in mouth, and optimised to accompany food, wines which truly match the undoubtedly great classed growth wines of Bordeaux. But the best of the wines tasted to support this review confirm that to achieve this goal, we must resist the market-pull of the American and Australian-influenced mass consumer, where bigger, oakier and sweeter is better, and instead insist on a distinctive New Zealand red wine style, namely subtle floral and aromatic wines of measurably high dry extract, achieved at the lowest alcohols possible, via reduced cropping rates. Those are still the key characters of great Bordeaux, which remains the measuring-stick for temperate-climate Cabernet / Merlot and related winestyles.

Acknowledgements: I appreciate the assistance of those winemakers who supplied wine, information, and particularly pre-release samples for this review. Information from Bob Knappstein (formerly of McWilliams Wines), Alex Corban, Dennis Robinson, Ian Clark, Paul Mooney and Gordon Russell has been greatly appreciated.

Cooper, M 1984: The Wines and Vineyards of New Zealand. Hodder & Stoughton. 203 p.

Cooper, M 2002: Wine Atlas of New Zealand. Hodder Moa Beckett. 288 p.

Kelly, Geoff 2007a: A Tasting of 1903 Lansdowne 'claret' ... www.geoffkellywinereviews.co.nz

Kelly, Geoff 2007b: Bordeaux and Hawkes Bay blends in New Zealand – the 2005 vintage. www.geoffkellywinereviews.co.nz

Scott, D 1964: Winemakers of New Zealand. Southern Cross Books. 100 p.

Thorpy, F 1971: Wine in New Zealand. Collins. 199 p.

© Geoff Kelly. By using this site you agree to the Terms of Use. Please advise me of errors.