Contents / Layout of this Review:

| # Introduction # Descriptors for Sauvignon Blanc # Key Descriptors for good New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc # Thiols # Background | # The Future # The Tasting # Acknowledgements # References # 8 Wines Reviewed |

New Zealand sauvignon blanc fruit at a typical level of ripeness, producing wines with clear varietal character, but still containing some methoxypyrazine / green capsicum notes. Depending on the ratio of berries just starting to show yellow, there will be suggestions of black passionfruit pulp fruitiness and red capsicum savoury character. See text. Photo: Kevin Judd.

Introduction

I have been thinking about New Zealand sauvignon blanc since tasting the first defective (H2S) 1979 Montana Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc, and then buying the triumphant 1980 edition, the wine which unarguably set New Zealand sauvignon blanc on its present course. And, as the person who first set out to characterise New Zealand sauvignon blanc, imperfectly, but it was 1987 (see below), I have been further thinking about this exciting New Zealand variety a good deal this year, in the (reflected) light of the Sauvignon Blanc Workshop and then the International Sauvignon Blanc Celebration 2016, 31 January – 3 February, 2016. At these meetings, Chairman Patrick Materman advises that up to 380 people gathered for a 1.5 day workshop on more technical aspects of sauvignon blanc viticulture and oenology, followed by 2.5 days of presentations and activities for the Celebration proper designed to illuminate the grape to a wider range of people.

Delegates to the Celebration had one formal sit-down tasting of eight sauvignon blancs from around the world, and access to a further 256 different sauvignon blancs from around the world in two associated events. Workshop participants studied 38 wines in their formal tastings. Some of these were experimental wines, fermentation trials and the like. Those who attended both events therefore could taste 302 different sauvignon blancs. Not all people attended both sessions, though. Perhaps 100 of these people were from overseas, New Zealand WineGrowers supporting some of them, so there was the potential for New Zealand to achieve wide reportage on our achievements with the grape.

It has to be said that 'wider range' of people was constrained by the fees for the entire proceedings exceeding $NZ2,500. The 'bible' for the event was United Kingdom winewriter Jamie Goode's masterly work The Science of Sauvignon Blanc, summarising the state of New Zealand sauvignon blanc research, and viticultural and winemaking practice. I am not sure what background and printed informative material was provided for the Celebration, but the Workshop had its own handouts, comprising skeletal summaries of the lectures, and data for the wines tasted. The tenor of the Celebration meetings can be gauged via the visual material Celebration speakers showed, and the excellent video-clips, both accessible at New Zealand Winegrowers' website. Key contributions are shown in the References list, below. It is to be hoped this archive stays on-line longer than the recordings for some Pinot Noir Conference ones have.

There is so much information in that fraction of the programme I can access, that we must hope there will be full documentation of both the Workshop and the Celebration, and in particular, very full documentation of the tastings. We could all learn a lot, if we had an informed guide to which of the many wines tasted in fact best showed the characters we do want, and equally, the characters we don't want. [[ Addendum, 19 May 2016: Julia Harding MW has posted her impressions of the Celebration, and tasting notes for 102 wines, under the title: NZ Sauvignon Blanc - more variety, less sugar, please at jancisrobinson.com (subscription needed for this article). She reports only on the New Zealand wines (sadly), scoring them from 14.5 to 18 (2), 31 of them scoring 17. I am not aware of any thorough New Zealand evaluation of the Celebration or Workshop tastings - an extraordinary state of affairs.]] But from first impressions, three intriguing snippets caught my immediate attention:

# Firstly, in terms of 'the New Zealand character' of our sauvignon blancs as presently offered, wines made from machine-picked grapes are measurably superior in terms of their key flavour components, when compared with hand-harvested grapes. This outcome of the scientific research programme has, needless to say, discomfitted many.

# Secondly, the assertion that New Zealand sauvignon blanc is well on the way to becoming the most studied and best understood grape in the world intrigued me. For example, asking Google the simple question "sauvignon blanc aroma" returns about 2,940 results. Without the quote marks, there are over half a million ! I would have to pencil in that that understanding at this stage is highly technical, and appears to not yet embrace critical components of wine quality and beauty (from an international standpoint) such as total dry extract, as well as some aspects of aroma and flavour which I enlarge on below.

# Thirdly, the stability of one of the key aroma and flavour thiol / chemical components in ripe sauvignon blanc, and the one which it seems many people love most in the young sauvignon blanc wine, turns out to be critically dependent on temperature of storage. This is the varietal thiol 3MHA that Prof. Paul Kilmartin characterises as 'sweet-sweaty, passionfruit'. He documents that if the newly finished and bottled wine is then warehoused (or shipped) at an average temperature of 18° or more, the half-life of this thiol can be reduced to three months. That is, after three months, half of it has gone. None may remain after two years. Conversely, if the storage temperature is 5°C, the wine retains 80% of this compound for 12 months, and the half-life is 21 months. The loss mechanism is via hydrolysis, rather than oxidation, so thankfully there is not the temptation to increase the SO2 at bottling, a factor which makes so many sauvignon blancs less pleasant in their first 9 months or so. The implications therefore for shipping through the tropics, where temperatures and containers may reach 30° and more, are critical for serious New Zealand wine producers. The researchers feel 10 – 12° would be an economic / practical compromise for temperature-controlled shipping.

Descriptors for Sauvignon Blanc

The main impression that emerges from the speakers and presentations on the website mounted by New Zealand Winegrowers is not a new one, namely that the distinctiveness of good New Zealand sauvignon blanc arises from its combining both 'green' smells and flavours, and fruity / tropical components. But immediately one has a caveat. The term 'green' was used constantly, but in my experience of critical wine evaluation extending over more than 45 years now, from a wine quality, pleasantness and satisfaction standpoint, there is all the difference in the world between green as in herbaceous (cut-grass / green bean), and green as in culinary herbes / savoury (sweet basil). This concept seems scarcely to have been discussed, but is I believe critical to the future defining and hence making of great New Zealand sauvignon blanc. A related lack was the failure to discriminate between the enormous sensory differences in red capsicum characters versus green capsicum, the former conveying an impression of ripeness and therefore being positive in the finished wine, versus the latter being so loaded with methoxypyrazines, and therefore unripe and negative beyond trace amounts. Hence the critical importance of differentiating between the two in defining sauvignon blanc winestyle.

Another aspect that is apparent to the wine-loving reader of these collected activities, is the extent to which wine researchers and wine consumers may exist in parallel universes. Some of the descriptors most-used by wine-lovers in talking about sauvignon blanc can scarcely be found in the scientists' lexicon. In wine science as elsewhere, presumably this is a result of there being some who will not acknowledge any research, investigation or documentation of a subject, no matter how original the work is, unless the information is both quantifiable, and published at the 'right address'. Top quality wine (as opposed to good and consistent commercial wine, even premium commercial wine) is more subtle than that, and well illustrates why 'scientism' falls short in the more complex aspects of understanding and defining wine quality. Matt Kramer (a speaker at the Celebration) has eloquently documented this topic this month, in an article titled: It's All Just Myths, You See: No data, no good, in Wine Spectator

By the same token some of the scientists' favoured terms are strange to the point of being obtuse. The most glaring example of this latter phenomenon is their wholesale adoption of the term 'box' (English) or boxwood (American) when referring to the smell of the foliage of the smallish hedge-shrub Buxus sempervirens, as a descriptor for aspects of the green character in under-ripe sauvignon blanc. In an increasingly urbanised world, how many people have in fact smelt box foliage, in New Zealand ? More importantly, is it wise to adopt an arcane European term such as this, when Wikipedia advises that in Europe, a percentage of the population find the smell specifically unpleasant. Further, the shrub is mildly poisonous. We are trying to promote the drinking of this wine, so adopting such a descriptor is seriously questionable.

To make matters worse, when the shrub is referred to as boxwood, or even more confusingly as 'box wood', the 'timber' (the plant is too small to have 'timber' as usually thought of, but the wood can be big enough for turnery) is odourless, so the supposed descriptor becomes even less appropriate. There are already plenty of more meaningful / much less obscure terms to describe parts of the spectrum of smells I understand to be implied by the term 'box'. They include snow-pea, cut-grass, crushed tomato leaf, crushed red currant leaf, crushed common broom tips, cut green bean, green capsicum, and in particular aspects of 'musky' including both 'armpit / sweaty' and 'cat's pee on a gooseberry bush', the descriptor so famously coined by the English.

There are at least three key reasons to abandon the use of the descriptor 'box' in sauvignon blanc research work. The first is that while the smell can include suggestions of the plant materials noted above, it does not illustrate them well as well as the originals. But in addition, there are further smells in the box aroma which are both unpleasant, and never found in wholesome wine. The key odour is related to rotting brown mushrooms, and fish guts (some species). Secondly, on a fine day, the plant and even its crushed foliage, scarcely smells at all. Thirdly, since we are striving to claim sauvignon blanc as New Zealand's signature grape (currently), it is undesirable to use a term with no New Zealand connotations whatsoever. Whereas with New Zealand's also-growing culinary reputation, foodstuffs-related descriptors are relevant. All in all therefore, it is hard to imagine a descriptor less appropriate for New Zealand sauvignon blanc research work than 'box', for a winestyle we as a country are striving to promote.

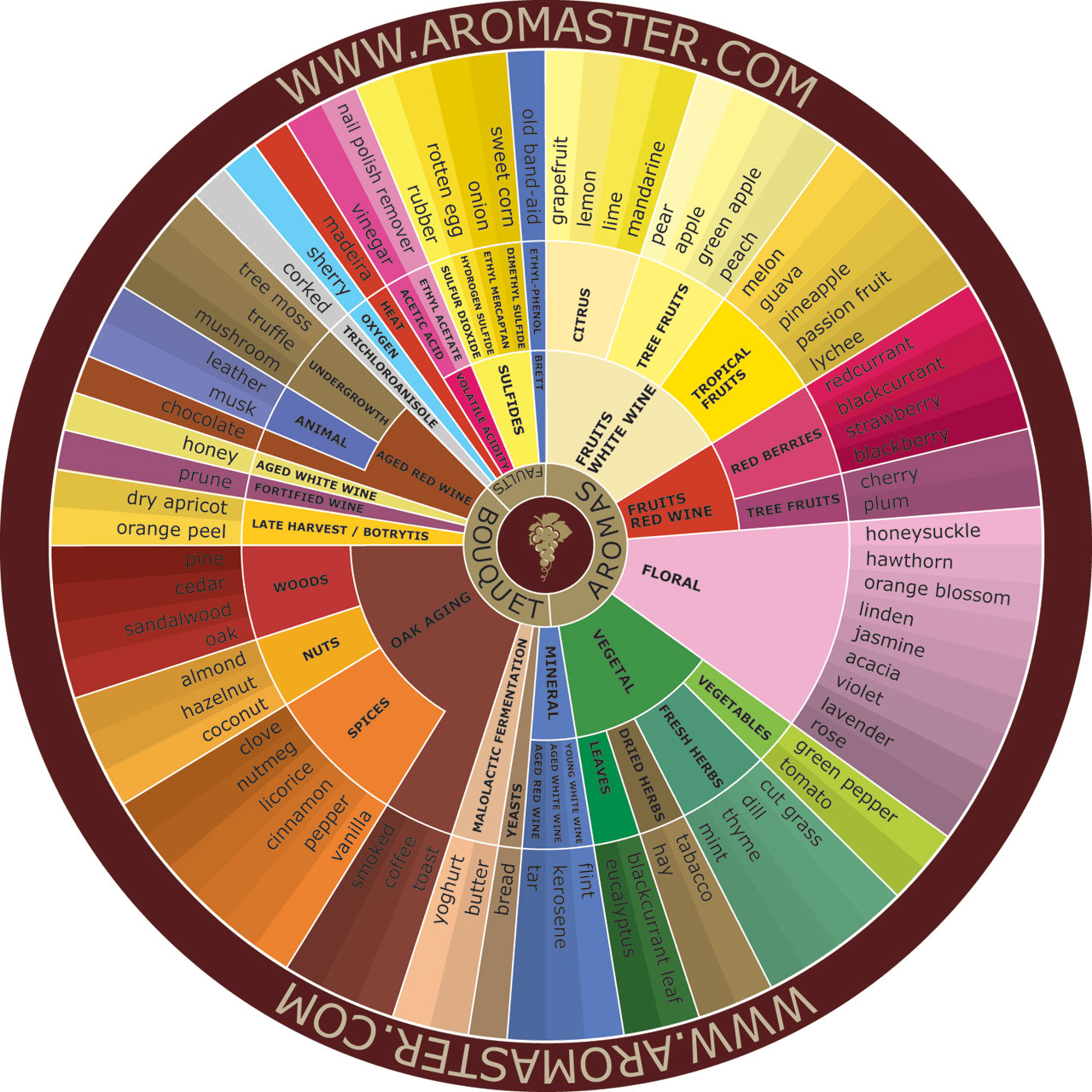

The place to start when adopting descriptors for wine research should be the pioneering and now widely-endorsed wine aroma and profiling work of Emeritus Professor Ann Noble, now retired from University of California, Davis. Her aroma wheel is for the moment illustrated in full on the Net, and can be purchased from her home site. It is based on familiar concepts, and universally known. It has also been the foundation for specialist aroma classifications for other wine styles. The New Zealand CRI HortResearch in conjunction with Auckland University has even developed an aroma wheel specifically for sauvignon blanc. There are now many derivative versions from Ann Noble's work, as for example this one which also looks good for wine:

Source: www.publicdomainpictures.net

As New Zealand sauvignon blanc emerges as one of the definitive winestyles of the world, in striving to characterise it we should adopt standard descriptors understood by the widest-possible span of both wine enthusiasts and researchers, as well as the all-important consumers. As is so often the case, a better result is achieved when scientists heed the real world.

Thus, it has long worried me that some descriptors I feel critical to the definition of, and characterising of, good New Zealand sauvignon blanc are not part of the wine researchers' thinking. To further clarify my views on this matter, for the tasting described below, I first set up 24 XL5 glasses with finely cut / virtually macerated samples (roughly a rounded teaspoon) of 23 perhaps-relevant plant materials. They are listed from sweeter / riper to less ripe / greener, noting that any order is arbitrary, with a comment where helpful. Those I think critical to the characterisation of modern high-quality New Zealand sauvignon blanc wine are in bold. 'Exact' means remarkably close to critical components of sauvignon blanc aroma, somewhere in the grape's ripening curve:

# cassis (in lieu fresh blackcurrant berries): relevant (in a tangential way)

# black passionfruit yellow pulp: exact, highly relevant, a key 'sweet-thiol' fruit descriptor, aromatic esters too

# apple (coxes orange): relevant, must include cut skin

# grapefruit flesh, Californian red: relevant, but scarcely 'citrus' in the New Zealand sense, much more tangy

# rhubarb stewed (sweetened): relevant to older sauvignon blanc

# cape gooseberry (Physalis peruviana): complex musky notes, beyond mango, too exotic

# grapefruit zest, Californian red: barely relevant, almost 'jaffa'-like 'citrus' yet a musky sweaty component too,

beyond New Zealand sauvignon blanc ripeness

# red tomato flesh and skin: relevant

# capsicum red: exact, highly relevant, key 'ripe green' and savoury descriptor precisely characterising 'exciting'

sauvignon blanc, very complex

# black passionfruit purple skin: exact, highly relevant, a key descriptor but much drier / more stemmy / more

phenolic than the pulp (naturally)

# sweet basil: exact, highly relevant, a key 'ripe green' and savoury descriptor also precisely characterising

'exciting' sauvignon blanc, very complex, captures the elusive 'herbes' concept

# red currant leaf: very relevant and totally different from white currant, 'sweeter', hinting at sweet basil

# black currant leaf: very relevant, different, musky, some reminders of sweet basil and black passionfruit skins

# capsicum yellow: exact, very relevant, less ripe than red capsicum, but closer to it than to green capsicum

# tomato leaf: exact, very relevant, complex

# snow-pea: exact, very relevant, much 'sweeter' than green bean

# cut-grass: just pure green, epitomises 'not winey' (NB these comments would NOT apply to high-linalool species,

eg sweet vernal, where the commonality between the grass sample, good riesling and ripe sauvignon blanc can

become startling). Cut-grass therefore not a good descriptor, character dependent on species

# common broom (Cytisus scoparius): exact, very relevant, a stemmy / slightly musky version of cut-grass,

virtually (?) no methoxypyrazines, good substitute for box since no adverse / non-winey component

# white currant leaf: very relevant at the cut-grass end

# cut green bean: very relevant but not all positive in a wine context, suggestions of methoxypyrazines

# capsicum green: exact, very relevant but not all positive in a wine context, excess methoxypyrazines

# celery: some relevance at the subliminal level, too strong, family Umbelliferae essential oils not part of sauvignon

blanc aroma

# box (Buxus sempervirens): hard-to-characterise green notes plus negative aromas clearly not related to wine (see text).

The negative attribute 'canned asparagus odour' is not discussed here, but in the section titled: The Future. For obvious reasons, the above exercise cannot easily be 'complete', quite apart from the vicissitudes of the growing season, and what is available at any given time of the year. To 23 of the samples including box foliage, I added a few mls of water. The 24th glass was also box foliage finely cut, but dry.

I cannot over-emphasise how revelatory the practice of finely cutting up plant (or other relevant) material, and putting it in an XL5 glass is. It transforms one's perception of the characteristic aroma, for the item being used as a wine descriptor. I find when I outline to tasting groups how I go about this, there is a measure of eye-rolling and general disbelief, how could anyone be so pedantic, but I urge readers to try this approach. A key factor is to totally clean the knife and cutting surface between each sample, and even so, leave all-pervasive plant materials such as green capsicum to last. Anybody who owns Le Nez du Vin will be familiar with how the 'green pepper' phial taints the whole box, if not kept separately. The sample must be cut as fine as is practicable.

Once the wine samples were poured, even though they were blind, I was then able to go back and forth between the wines and the plant materials, and get a much better impression of where each fitted in. And the simplest summary is that all but one of the plant materials seemed relevant to the wines, to a greater or lesser degree. Surprisingly, when smelt in this manner and in this context, even improbable materials such as red tomato flesh do display some winey connotations. And some, particularly sweet basil and red capsicum, are absolutely critical components of ripe high-quality sauvignon blanc aroma, though thus far overlooked. The exception, the one that is at the negative end, but doesn't really fit in, is box, for the reasons already given.

Key Descriptors for good New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc

Noting that in the traditional view, good New Zealand sauvignon blanc is characterised by its harmoniously contrasting 'green' and 'tropical' aroma and flavour components, nonetheless over the last 35 years total style appreciation for sauvignon blanc (apart from in the United Kingdom) is moving towards the riper end of the sauvignon blanc ripening curve. In my view the traditional documented summary of New Zealand sauvignon blanc appreciation completely overlooks its most exciting dimension, namely the 'savoury herbes' component.

New Zealand sauvignon blanc fruit showing much greater berry ripeness. When picked at this stage the wine will almost certainly show black passionfruit pulp fruit aromas and flavours, plus red capsicum savoury characters and zip. The trick is to not lose the fresh character people so value in New Zealand examples of sauvignon blanc the wine, so only a percentage of the crop may be left to ripen to this stage. See text. Photo: Kevin Judd.

The key concepts for understanding the better and increasingly fine New Zealand sauvignon blancs, both for the wine and therefore wine research, seem to me to revolve around the following descriptors. They are in rough order of importance, starting with the most desirable / characteristic / positive for New Zealand and particularly Marlborough wines. They suggest a kind of ripening curve for the grape:

# black passionfruit pulp and its sweet yellow near-tropical yet also nearly aromatic / piquant smells and flavours,

including the concept 'sweet thiols' as well as fruity esters. NB: the exhilarating intensity of aroma in New Zealand

black passionfruit pulp is rarely seen to the same degree in other countries;

# red capsicum and sautéed red capsicum smells and flavours, bespeaking complex aromatic / phenolic ripeness,

and embracing a savoury and 'herbes' component, yet not 'sweet' in a fruity sense;

# black passionfruit purple skins with their more complex and more phenolic aromas (also suggesting terpenes)

and flavours, but no sweetness;

# sweet basil aroma and flavour exactly reflecting 'savoury herbes' complexity (NB: NOT herbaceous), as with

the concept red capsicum accurately bespeaking aromatic / phenolic / fruit ripeness, and in addition communicating

(to the taster) as very 'winey' and food-friendly. It is this component (with red capsicum) that makes sufficiently-

ripe sauvignon blanc the wine so extraordinarily versatile with food;

# white nectarine flesh and its magical purity of ripe and subtle white-fruit smells and flavours;

# white honeysuckle flower aroma in riper grapes, highly desirable but elusive;

# a citrus component, needing more work to define;

# English gooseberries both raw but properly ripe (that is, red colouring showing), and cooked;

# elderflower aroma as the primary floral note in sauvignon blanc grapes 'just' ripe enough, but it is both subtle and

rarely identified;

# English gooseberries at the green to yellowgreen stage (i.e. as more commonly known), raw and cooked. This is

the Sancerre analogy;

And then in trace amounts adding the refreshing counterpoint notes New Zealand sauvignon blanc is famous for, but

these must not be overdone: the decreasingly ripe sequence through:

# yellow capsicum smells and flavours reflecting an intermediate stage of phenolic (and methoxypyrazine) ripeness;

# snow-pea, intriguingly 'sweet' as well as green;

# common broom tips, a stemmy, slightly musky and therefore more winey version of cut-grass aroma / flavour

# green bean aromas and flavours for some methoxypyrazine components, only trace needed;

# green capsicum aromas and flavours for strong methoxypyrazine components, only trace needed.

Plus the all-important musky-thiol notes characterised by the concepts:

# 'armpit / sweaty', 'musky thiols' (as suggested below), threshold levels only

# 'cat's pee on a gooseberry bush', including 'musky thiols' (as suggested below), threshold levels only.

Though the latter two are last in what must be a personal ranking, nonetheless they are critically important in characterising New Zealand sauvignon blanc, particularly when in threshold or preferably subliminal (literally) amounts. 'Subliminal' varies widely from individual to individual.

Note this schedule does not take into account the desirable further aroma, flavour and texture complexity factors arising from barrel fermentation in old or new oak, plus or minus lees autolysis and batonnage. Nor does it acknowledge the concept of the trendy but ill-defined concept of 'minerality' in the wine, mainly because that perception is all too often in fact a function of the interaction between pH and total acid on the one hand, or subliminal reduced simple sulphurs, on the other. It is probable that there is in fact a concept 'minerality' in its own right in wine, in the sense that wines (good white wines particularly) from calcareous soil parent materials can seem to taste different. There is an analogy here with wines showing above-threshold sodium. 'Minerality' in wines is yet another of those wine terms much more used than understood, and can therefore in fact be unhelpful in trying to characterise wine smells and flavours.

Only the British market wants sauvignon blanc wines dominated by the characters at the green end of this sauvignon blanc ripening curve. We must not let that eccentric market deflect us from the goal of creating ever more beautiful, complex and satisfying subtly-ripe sauvignon blanc wines better reflecting the concept 'ripeness' in sauvignon blanc, which as the above list suggests, is complex. Such wines will increasingly meet with international approval.

Thiols

There can be no doubt that thiols (sulphur-containing volatile and odoriferous organic molecules) are a key component of the characteristic New Zealand sauvignon blanc aroma and flavour, as they are for other 'exciting' food items such as blackcurrants and guavas. I am not using chemical names in this review any more than I can help, since they are beyond my ken. But since some of the publications use only the full chemical name, some scientists being like that, here is a synonymy for the key thiols emerging from the sauvignon blanc research:

3MHA = 3-mercaptohexyl acetate = sweet / sweaty passionfruit * pulp = perception threshold 4 ng/L

3MH = 3-mercaptohexan-1-ol = passionfruit * skin / citrus / grapefruit = perception threshold 60 ng/L

4MMP = 4-mercapto-4-methylpentan-2-one = cat's pee / broom tips odour = perception threshold 0.8 ng/L

Notes:

* meaning black or purple passionfruit (Passiflora edulis)

# Individual human perception thresholds vary enormously from person to person

# a nanogram is one billionth of a gram

# a microgram is one millionth of a gram

# a milligram is is one thousandth of a gram

# One thousand grams = one kilogram = 2.2 pounds

# To illustrate the aroma potency of some of these chemicals, one milligram of 4MMP is detectable (by good tasters) when diluted in 1 million litres of water.

# The concentration of these flavoursome chemicals in the wine (or even the neutral test solution) profoundly affects the way it is interpreted by the taster, so much so that quite different descriptors may be offered for the same compound, at varying levels. This is yet another finding in the wine aroma research work at Auckland University. When that observation is coupled with the wide variation in taster thresholds, it is not a surprise that achieving agreement on wine descriptors is difficult.

The other nett impression I gained in reading through some of this literature, is that the term 'thiol' in a sauvignon blanc wine context is in peril of becoming a kind of portmanteau word, in New Zealand sauvignon blanc thinking. Apart from the wine science researchers, it is I suspect another wine term much more used than understood. Only those who have access to a sniffer port on GC-MS equipment really know what they are talking about, when it comes to thiols. As a small step in trying to simplify this issue, at the non-technical / wine enthusiast level, I suggest we sort our thoughts a little more, and refer to three kinds of thiols, rather than the one blanket term 'thiol':

sweet thiols: key components of positive wine aromas, as seen in black passionfruit pulp, and to a degree black passionfruit skins, noting they are augmented by esters;

musky thiols: aromas positive only in trace / threshold amounts, as in the concept 'armpit' character (bacterially-degraded sweat), and the English notion of 'cat's pee on a gooseberry bush';

sour thiols (or reductive thiols): smells and flavours with a clear reduced-sulphur component, clearly a negative aroma and flavour feature for a majority of tasters (but not all), and sour and hard on the palate as well. Many examples probably owe their character as much to plain sulphur reduction as thiols.

It must be emphasised that wine is such a complex mix of aroma and flavour-containing molecules, that any tip-toeing classification such as the thoughts above, is merely indicative. Jamie Goode's work summarising the 'pure' research highlights the extent to which one family of molecules augments another, and the fact that trace amounts of chemicals not able to be smelt alone do react synergistically in the wine, to become clear contributors to its character.

Background

Nearly 30 years of tasting and thinking about New Zealand sauvignon blanc have passed since I essayed the first characterisation of the grape and its character in New Zealand. This appeared in the first issue of Cuisine magazine, where I set out to define all the New Zealand wine styles of the day. This had not been done in any systematic way at all, up to that point. Needless to say it is a fumbling account, and it reflects the fact that most sauvignon blanc wines then were much less ripe than they are now, and the cropping rates were even higher than they are now. I wrote two articles about sauvignon blanc in that issue, the first titled 'Sauvignon blanc steals the limelight', pp 82 – 84, celebrating the success of the grape up till that point, the other a description of the grape in a schedule characterising the main New Zealand winestyles in 1985 – 1987, variety by variety. The sauvignon blanc part of the latter is reproduced below:

SAUVIGNON BLANC [ from Cuisine Issue 1, January/February 1987: p. 89 – 90 ]

Sauvignon Blanc looks set to become one of the top varietal whites in New Zealand, as discussed on pages 82 – 84. It has strong varietal character in our climate and, rather like Cabernet Sauvignon, it needs to be ripe to achieve pleasing and harmonious flavours, although it allows more latitude than its red relative. The winemaker may choose to pick it at the aromatic, green capsicum stage of ripeness of about 18 to 21° Brix to make the fresh, even aggressive, style epitomised by the 1984 Selaks Sauvignon Blanc. Alternatively, in premium viticultural districts such as the east coast belt from Hawke's Bay to Marlborough, where there is reduced risk from leaving fruit on the vine, the grapes may be ripened to the 22 – 24° Brix level. Such grapes develop very attractive and relatively more subtle red pepper and floral honeysuckle smells and a more satisfying flavour. Some winemakers pick part of the crop early, and the rest later, and by blending achieve maximum bouquet and palate.

The key to great Sauvignon Blanc is this crisp, complex fruit flavour containing suggestions of both green and red capsicums, honeysuckle flowers and herbs, which combine with the fresh acid to give a wine of great zip and character. Under-ripe wines can be aggressively grassy and green capsicum-like in both smell and flavour with austere, flinty acid flavours which are unattractive.

Sauvignon Blanc is being made in three main styles, all offering a marked contrast to Muller-Thurgau. The first is a crisp dry, highly varietal wine, bottled straight from stainless steel. It is very similar to some of the best Loire and Sancerre wines from France. The style is distinctive among New World wines. The Montana Marlborough series since 1980 has been world class. Other outstanding wines have come from 1983-85 Corbans, including the 1986, 1984-86 Selaks, 1984 and 1986 Dry River, and 1985 Seifried. Sometimes this style is too acid for the uncommitted. The slightly sweet version is thus popular, as in the 1984 Penfolds, and is proving a good way of attracting people to the variety.

The second style involves very careful use of new oak, and residual sweetness below the level it is tastable, to delicately counterpoint the very fresh smells and flavours of the grape. New oak in small amounts both mellows and lengthens the flavour. Some of these wines are so subtly oaked, it is not possible to be sure it is there. These ultimately will be our greatest sauvignons, in terms of world recognition. 1985 Corbans Fumé Blanc is the finest thus far made, in terms of introducing finesse into such a strongly flavoured variety. Only a whisker behind is the Cloudy Bay wine, and the Selaks Sauvignon/Semillon blend.

The third group comprises the obviously oaked wines, commonly labelled in the Californian fashion as Fumé Blanc. They may incline more to the white burgundy style, and may be richer and softer. Some have Semillon blended with them, to help round them out. These wines cover a wide spectrum. To one side are the under-ripe rank wines propped up with oak. On the mainstream they extend from crisp oaked wines such as Neudorf Fumé Blanc, via softer flavoursome wines as pioneers by Cooper's Creek and followed by Ngatarawa and Hunter's, through to the remarkably rich Morton Estate black label Fumé Blanc. Provided the fruit is ripe and long-flavoured, these Fumé styles can carry a surprising amount of oak. Some wines are however so flavoursome they are hard to match with food.

There is therefore tremendous diversity to be found in New Zealand Sauvignon Blanc. Some producers, for example Hunter's, thoughtfully produce a stainless steel version as Sauvignon Blanc, and an oaked version as Fumé Blanc. When both are made from the same base wine, this makes learning about oak easy. As a varietal group of wines, they are well worth exploring. Sauvignon flavours will also be found in other wines. Rather like Gewurztraminer, Sauvignon Blanc has so much character that it is well suited for use as a blending variety to add flavour and punch to simple base wines. It is particularly suited to chablis styles and makes them refreshingly different from riesling styles.

SUITED TO: Seafoods, salads, smoked foods.

CELLARING: 1 – 3 years from vintage.

OTHER NAMES: Fumé Blanc, Blanc Fumé.

The Future

For the future, the key attributes of the grape, the qualities of its chemistry, aroma and flavour which are so distinctive in New Zealand, are a function of our singularly temperate climate, high UV radiation, and marked diurnal temperature range. We can therefore expect to see high-quality sauvignon blancs emerging in ever-greater volumes from not only Marlborough (with increasing emphasis on the Awatere Valley), but also from Waipara, and Central Otago. The Waitaki Valley vineyards remain an enigma in this context, but given global warming on the one hand, and the windiness of the Awatere Valley on the other, it is conceivable they too may provide workable sauvignon blanc sites. Steve Smith MW however advises that thus far, the district is much too cold.

The most important next step in making New Zealand sauvignon blanc a great but more serious wine of the world, in addition to the distinctive but near-mass-consumption beverage wine it is now, is the need to add body, texture, dry extract and complexity to the already (at best) distinctive aromas and flavours. That will first and foremost require reducing cropping rates by up to an order of magnitude, to achieve dry extract values more appropriate by international fine wine standards, and then in the longer term, the subtle and judicious use of oak. There will be two main winestyles there, one more subtle via barrel fermentation and lees work in older oak, the other a bolder (and in some ways) more French approach via new oak, again with varying approaches to lees work. The MLF fermentation will be an independent / optional variable in both these approaches. It seems unlikely that 'characteristic' New Zealand sauvignon blanc will involve much use of malolactic fermentation, but it is also certain that a whole new family of New Zealand sauvignon blancs utilising MLF and these more sophisticated approaches to élevage await discovery. Cloudy Bay's Te Koko has been the bellwether wine for all these concepts, itself having varied considerably as the winemakers tried one tack, then another. To crystallise the emergingly distinctive New Zealand sauvignon blanc winestyle (as defined in this review) in public estimation will require critically and appropriately ripe fruit, not an uncritical assumption that green is best, and clean, not wayward, approaches to fermentation (as further discussed in the Wairau Valley Reserve and Southern Clays Reserve wines, below).

In an immediate response to this article, however, Jancis Robinson MW by implication raises the questions: why do so many New Zealand sauvignon blancs in the United Kingdom market smell and taste of canned asparagus, and why do I not include this negative flavour component in discussing attributes of the grape. An oversight in one sense, in that subconsciously I was writing about descriptors for 'good' and young sauvignon blanc. The canned asparagus odour develops with time, and reaches threshold level usually after 18 – 24 months or so, mostly in wine made from under-ripe fruit. This aroma is intimately involved with the development of dimethyl sulphide in the wine. However it seems likely to me there is more to this character than just dimethyl sulphide, to account for the 'green' component. Since wine made from under-ripe fruit is more likely to develop the odour, and such wines have higher levels of methoxypyrazines, it is hard to ignore them in this context. The whole topic is one for which there are not yet answers. Dr Rebecca Deed of the Auckland University wine science research group advises that degradation pathways for development of canned asparagus odour are currently being actively researched.

Robinson's observations pinpoint three critical issues for New Zealand winemakers:

# Production of the canned asparagus odour is much more likely in wines made from over-cropped and thus under-ripe fruit. This bracket is highly likely to include wines made to a price for overseas markets, some for supermarket BoB labels, some shipped in bulk, and bottled offshore. Many decry this latter practice as not being in New Zealand's long-term interests;

# Production of dimethyl sulphide-related odours is more likely in wines made by winemakers pursuing high-thiol (and hence more reduced sulphur molecules) wines of the kind I decry later in this review;

# Production of dimethyl sulphide is markedly increased by high storage temperatures, leading both to the degradation of positive flavour compounds such as the passionfruit aroma thiol 3MHA, and hence the greater perception of negative compounds. Therefore the temperature at which New Zealand sauvignon blanc wines are warehoused, and particularly shipped to the northern hemisphere, is critical. Clearly cheaper wines are more likely to be shipped without expensive temperature control, leading to the worst of all sauvignon worlds.

Pursuing this a little further, a quick check of half a dozen export-oriented New Zealand wineries shows that remarkably few in fact require temperature-controlled shipping to the northern hemisphere. J F Hillebrand Global Beverage Logistics confirm that impression. The latter further advise that for the better (that is, less risk of being stuck in a hot Asian port) Panama route to London, temperature inside the cartons in a standard 20ft container fitted with VinLiner may be at or above 30° C for 18 or 19 days. This figure is horrifying, in terms of the stability of the key thiol flavour component 3MHA in sauvignon blanc. It means that few northern hemisphere customers are seeing New Zealand sauvignon blanc wines at their best. Apparently only the Japanese market systematically demands shipping in temperature controlled containers. And checking a little further, a quick check of half a dozen London merchants shows that a distressingly high proportion of their New Zealand sauvignon blanc stock is vintages older than 2015, by which time many wines will be losing freshness, even if they had had optimal shipping. But few have. So the probability of buyers ending up with less than optimal New Zealand sauvignon blanc wines in most export markets is high. And thus full-circle back to Robinson's observation.

Robinson has thus put her finger on a key deficiency in the New Zealand approach to exporting wine. At the moment, many wineries leave it to the buyer to decide if the wine is shipped with temperature control. In my view, New Zealand wineries need to be much more proactive in specifying temperature-controlled shipping across the equator, in the same way as discriminating New Zealand wine importers do. The difference in cost is in the order of 60% for a standard 20-foot container, which works out at roughly 60c freight per bottle instead of 40c, to the United Kingdom. The pay-off in terms of enhancing and optimising the quality and thus reputation of temperature-fragile New Zealand sauvignon blanc for all northern-hemisphere export markets makes this a no-brainer. And the research data document why. Wineries need to take the initiative on this matter, rather than as now, passively leaving it to the importer to decide in terms of their reputation as a merchant whether they will specify temperature-controlled shipping. The quality and future growth-potential of good New Zealand sauvignon blanc demands no less.

The Tasting

This review would ideally have been based on a New Zealand-wide tasting of sauvignon blancs, or critical review of the Celebration and Workshop wines. We will have to hope that something thorough emerges from one or other of the 380 attendees, who had the opportunity to taste 302 sauvignon blanc wines during the meetings [[ 19 May 2016, see earlier Addendum ]]. Instead this article was stimulated by the imagination and generosity of the Villa Maria wine group, notably Ian Clark and George Fistonich, who thought I might like to know more about their sauvignon blanc operations in Marlborough, and taste again all their 2015 Villa Maria Reserve and Single Vineyard wines, since I had been quite abrupt about one of them, last year. Since any wine assessment exercise benefits from making comparisons, and tasting strictly blind, for my second follow-up blind tasting back in Wellington, I added in the widely-recognised 'definitive' New Zealand sauvignon blanc, Astrolabe's Awatere Valley bottling, both the 2015, and the 2014 to add perspective.

Acknowledgements

Villa Maria Wines, through the good offices of Export Manager Ian Clark, generously facilitated my visit to Marlborough, in April. Prof Paul Kilmartin of the School of Chemical Sciences, Auckland University, kindly made available to me his masterly presentation to the Sauvignon Blanc Workshop programme. Dr Glen Creasy, Senior Lecturer in Viticulture, Faculty of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Lincoln University, and Kate Radburnd and Julianne Brogden [ then ] of Pask Winery (the latter also of Collaboration Wines) helped me with the handout material for the Workshop. Dr Rebecca Deed also of the School of Chemical Sciences, Auckland, not only checked my manuscript for appropriate interpretation of the technical reference material, and use of technical terms, but also patiently answered questions. Vicki Metcalfe of JF Hillebrand (NZ) went out of her way to help with shipping information. Wineries contacted on this matter were without exception helpful too. It is a particular pleasure to have this review illustrated with photos kindly made available by Kevin Judd, the man who first put New Zealand sauvignon blanc (and Cloudy Bay winery) on the world stage, starting in 1985. That is not to say that any of these people agree with or endorse any of the more general observations I make about sauvignon blanc in New Zealand.

References

Goode, Jamie, 2012: The Science of Sauvignon Blanc. Flavour Press, 134 p. [ Part of New Zealand Winegrowers' levy-funded research programme.' ]

Goode, Jamie, 2016: Thiols and beyond: the Science of Sauvignon blanc. [ Reference and visual material presented to the 2016 Celebration, 21 p, succinct ] www.nzwine.com/assets/Presentations/Sauvignon%202016%20Jamie%20Goode.pdf

Goode, Jamie, 2016: The Science of Sauvignon Blanc. [ video of lecture to the Celebration, 19 minutes, a superbly accessible summary ] www.youtube.com/watch?v=8dSZkSxCscg

Kilmartin, P, 2016: Thiols found in Sauvignon blanc and their significance. Paper and visual material delivered to the 2016 Sauvignon blanc Workshop, 31 Jan, 2016. 57 p. [ An immensely rewarding manuscript summary of this technical topic.]

Kramer, Matt, 2016: It's All Just Myths, You See – No data, no good. Wine Spectator: www.winespectator.com/webfeature/show/id/53034

Parr, Wendy, 2016: From "the importance of green" to matters more complex: 10 years of Sauvignon sensory research. [ Reference and visual material presented to the 2016 Celebration, 15 p, more technical ] www.nzwine.com/assets/Presentations/PARR_PDF_Sauvignon2016%20PPT.pdf

Parr, Wendy, 2016: Ten Years of Sensory Sauvignon Research. [ Video of lecture to the Celebration, 18 minutes, more technical ] www.youtube.com/watch?v=wLY5JnL83Io

THE WINES REVIEWED:

Beautiful lemongreen. This is the cleanest, sweetest (on bouquet), most complex, and most rewarding of the six Villa Maria Marlborough Reserve and Single Vineyard Sauvignon Blancs in the 2015 season. The bouquet includes elderflower and dominant notes of white nectarine, black passionfruit pulp, pure white clover honey, and sautéed red capsicum, plus a critical and defining undertone of sweet basil. These are some of the key descriptors for great New Zealand sauvignon blanc, looking ahead. [ The fact that the British market wants something less ripe and less magical is irrelevant. We can easily cater to their taste eccentricities with less ripe / greener-tasting fruit.] In this wine, it is the sweet fruit plus savoury herbes complexity (sweet basil) which makes it (literally) mouth-wateringly appealing. One sniff and the wine cries out for appropriate foods. Follow-through from bouquet to palate is rewarding too, the wine having just enough body and substance to both be pleasing in mouth, and good with food. This body and substance issue, or dry extract as I have been commenting about for red wines in New Zealand since the 1980s, is the key failing of so many New Zealand sauvignon blancs. The reason is simple. In New Zealand they are (in general) cropped at twice (or more) the tonnage per hectare when compared with the leading sauvignon blanc appellations in France, where harvest is constrained by the Appellation Controlée regulations. Even so the persistence of flavour is good, with pure fruit in which very ripe English gooseberries can be recognised too. This wine shows great judgement in timing of picking, and provides a model reference wine for the industry. By classic French standards, it could be richer. Cellar 3 – 8 years, but it will hold longer for those not obsessed with the bizarre single-factor New Zealand fad for dismissing sauvignon blanc as too old after 18 months. GK 04/16

Lemon, not quite the perfect green wash of the Taylors Pass wine. Bouquet is very close to it, however, reflecting a welcome return to form for this label after a (relatively – for Astrolabe) disappointing 2014. There is a gorgeous yellow honeysuckle complexity note here, on similar nectarine and black passionfruit pulp fruit, and sautéed red capsicum. This wine too has the magical sweet basil complexity note seen in the Taylors Pass wine, but in addition it hints, merely hints note, at trace musky sweat / armpit aroma. This is a musky thiol character I'm generally down on, but at this level it melds almost insensibly into black passionfruit, as much the purple skin as the yellow pulp. Palate is aromatic and lovely, drier than the Taylors Pass [ confirmed ], and arguably therefore the superior wine. This wine too is a model New Zealand sauvignon blanc, as year in, year out, one or other of the two Astrolabe Sauvignon Blancs from the Wairau or Awatere Valley invariably is. Note however this wine illustrates a near-maximum desirable level of the armpit complexity character. It is worth repeating that the offensively sour sweaty wines which won gold medals in the first few years of this century were an absolute judging aberration, which threatened to derail New Zealand sauvignon blanc. Cellar 3 – 8 years. GK 04/16

This is one of two distinctly yellow-washed lemon-coloured wines in the Villa set. Bouquet on this wine is intriguingly different, combining clear sautéed red capsicum notes with yellow fruits reminiscent of both black passionfruit pulp and almost trace mango. As with the Taylors Pass wine, there is a suggestion of pure white clover honey, too. (NB: pure New Zealand clover honey is white, and has virtually no smell, just a very sweet white waxy / honey character. Virtually all our 'clover honey' has colour, aroma and flavour blended into it from other nectar / pollen sources). In mouth this wine seems both fractionally sweeter [ confirmed ] and riper than the first two, still aromatic from the black passionfruit component but scarcely any recognisable red capsicum complexity. Nectarine / stone fruit is the main impression, with few green notes at all. The British would therefore condemn it, but here in New Zealand it bridges the gap to the best Hawkes Bay sauvignon blancs, via Martinborough. Only on the late aftertaste do suggestions of red capsicum zingy aromatics become apparent. NB: this wine is as sweet as top-quality New Zealand sauvignon blanc should be. Cellar 3 – 10 years, being riper. GK 04/16

Good lemongreen like the Taylors Pass wine. After the top wines, immediately there is a step down in perceived ripeness, sweetness, and fruit complexity here. The first impression is mixed capsicum, centred on yellow capsicum, some red, but with threshold notes of green capsicum, snow-pea and green bean. The latter three characters are either desirable complexity notes (from a British standpoint, and only a British standpoint), or serve to make the wine just another unappealing Marlborough sauvignon blanc … for those less attracted to green flavours / less-ripe sauvignon blancs. In mouth the green notes increase, with seemingly green 'phenolics' (as in green capsicum, so methoxypyrazines in fact) developing on the tongue, and lingering to the aftertaste, where the suggestions of cut-grass / green bean are more apparent. The latter are part of the undesirable 'box' descriptor the sauvignon blanc scientists like to refer to. Residual sweetness is a little higher than some, as if to mask these green attributes. There is still quite good fruit weight. This is a wine to divide opinion, as to its merits. The English would like it. GK 04/16

Lemon with a straw wash, clearly a little older than the other seven wines. Bouquet is intriguing, the primary year-one sauvignon blanc thiol-derived fruit characters now fading and melding into a mix of black passionfruit skins, stewed less-ripe (i.e. not red) rhubarb stalks, and bottled quince, with an indeterminate musky note. Greengage plum is part of it, too. Flavours likewise lack the immediate fresh-fruit analogies of 9 – 15-month-old sauvignon blanc, but are still attractive in their own clearly-different right. Length of flavour is particularly good, the greengage part developing now, the phenolics offering some reminders of sucking on greengage plum stones. That would probably correlate with a fading red capsicum component. Finish shows beautifully judged residual and fruit concentration, the wine perhaps reflecting a fractionally lower cropping rate than the Villas. Cellar 2 – 6 years. GK 04/16

Good lemongreen like the Taylors Pass wine. Bouquet in this wine is closest to the Clifford Bay Reserve, but fractionally less ripe. It therefore shows yellow and green capsicum notes rather more than red, with suggestions of snow-pea grading to trace green bean. It is beautifully clean though, in that style. Palate shows similarly good richness to all these sauvignon blancs, nicely balanced residual sweetness, and considerable length. Flavours however are clearly greener, centred round yellow capsicum and snow-peas, but some green capsicum too. There is still a savoury note suggesting sweet basil, lengthening the flavour. This is a hard wine to score, the assessed ripeness being scarcely silver medal level, whereas the concentration does merit silver. This ripeness level does not cellar well, developing canned asparagus characters after 18 – 24 or so months. GK 04/16

This is the second clearly yellow-washed lemon-coloured wine. It is also one of the two in the set showing reductive thiols to a debatable degree. Depending on individual sensitivity to reduced sulphur molecules, tasters will vary widely in their tolerance / acceptance of the reduction in this wine. Like the Southern Clays wine below, this Wairau Valley Reserve falls into the less desirable class of New Zealand sauvignon blancs. Behind the clogging reduction there are clear yellow / mixed capsicum fruit notes, and suggestions of English gooseberry. Fruit ripeness is probably slightly ahead of the Graham Single Vineyard wine, but flavour is rendered harder and more sour by the entrained reductive thiols. By the same token the aftertaste is long, but if that length is too dominated by components not in the desirable spectrum of flavours, this is a mixed blessing. Fruit concentration is good, and the residual is attractively balanced. This wine will probably to a degree 'grow' out of its sulky nature in cellar, for those who like older sauvignon blancs. Cellar 3 – 8 years.

This is a significant wine in the hierarchy of New Zealand sauvignon blancs, but not necessarily for totally commendable reasons. It was a gold medal winner and then Champion Sauvignon Blanc in this year's Royal Easter Show Wine Awards 2016. This result highlights how wine shows and wine judges are not infallible, largely for the reason that wine judges get carried away on fads and fashions in the same way as the public at large. And judging being democratic / by consensus, there is a point beyond which dissenting voices cannot be heard, if the harmony of the judging panel is to be maintained. Therefore Villa Maria must study this result carefully, and take on board that a significant percentage of the population find the characteristics showing in this wine (and becoming intolerable in the Southern Clays Reserve wine), either unpleasant or disgusting ... depending on the person and their individual threshold to reduced sulphurs. All the talk in the world about 'thiol complexity' is irrelevant to them. So a judging result like this must not become a direction in which to move winemaking. Rather the reverse.

It is worth pausing at this point, and checking what the winemakers see in this wine. They say: "A classic Wairau Valley style bursting with the trademark ripe fruit characters found in this sub region. The nose displays pure and powerful aromas of passionfruit, grapefruit, blackcurrant, and underlying subtle flinty tones. The palate is concentrated with an enticing array of ripe gooseberry and guava flavours, naturally complemented by a fine thread of acidity and a long finish." There is clearly a gulf here between perception and reality. Only the words 'underlying subtle flinty tones' give some hint (by way of euphemism) to the characters I am objecting to. Their wording seeks to ride on the nebulous wine concept 'minerality'.

But it is not only winemakers who need to be careful with judging results like this. Judges themselves need to think a good deal more carefully. This wine in effect intentionally sets out to diminish or destroy the intrinsic beauty of the grape and its juice by imposing winemaker-induced artefacts on the finished wine, artefacts which are negative for a significant percentage of consumers. The fact that some consumers and wine judges are not sensitive to this artefact / this defect is irrelevant. If wine competitions reward wines like this, those winemakers striving to make wines which optimise the beauty of the grape, which more or less by definition will include this country's very best and most internationally worthy and exciting examples of the grape, will be dismayed at the least. In some cases they will wash their hands of judging, and cease to exhibit. The nett result will be that wine judging, which being rooted in the Agricultural and Pastoral Shows tradition, is intended ultimately to 'improve the breed', will in fact become less and less relevant. Already there are too many wineries, some of which are industry leaders, who do not exhibit. This wine, and particularly the Champion Sauvignon Blanc judging result, provides an illustration of why. All food for thought, therefore. GK 04/16

Lemongreen, like the Taylors Pass Reserve wine. One sniff of this wine and it is simply unacceptable, on account of its intense reductive thiols and other sulphide notes totally masking the quality of the fruit. The fact that wines like this have won gold medals does not validate this bizarre wine style, where intentional winemaking artefact destroys the beauty of the fruit. It is worth noting that in wine judging where winemakers may dominate panels, the whole process of judging / assessment can be derailed by fad and fashion – where a strong judge presumably with a personally-high threshold to reduced sulphurs wants to endorse wine styles like this. Both chardonnay and sauvignon blanc are at this moment suffering from this mistaken aspect of the judging process in New Zealand. The result is wines which many people find simply disgusting are being given gold medals. There is no quicker way to discredit the relevance of the entire judging process, as discussed more fully for the Wairau Valley Reserve wine. It is a total mistake to tolerate the qualities this Southern Clays wine shows.

Beyond the reductive thiols and reduction, on smell you can hazard a guess that the wine is made from sauvignon blanc fruit. In mouth that supposition becomes clearer, with good richness and length based on mixed capsicum flavours. There are possibly some better fruit qualities too, but you simply can't tell, the wine being so clogged, hard, and sour from reduction. As noted elsewhere, these attributes lengthen the aftertaste too, but not positively. This wine represents a lost opportunity, in terms of consumer satisfaction. The only good aspect to a wine like this, in the context of the Villa Maria wine company where it is more than evident from other wines in their portfolio that the wine has been made in this style by design, is that the winemaker can equally well avoid the style, once its 'values' are perceived more accurately. There are other companies not so fortunate. Not worth cellaring. GK 04/16

© Geoff Kelly. By using this site you agree to the Terms of Use. Please advise me of errors.